Last year, nearly 108,000 people in America died from drug overdoses. In Cook County, the number of opioid deaths was twice that of gun homicides. Substance use disorders are devastating families, draining cities of economic productivity, and diverting criminal justice resources away from violent crime.

To tackle drug crises, policymakers have traditionally turned to the justice system, and assumed its role is to threaten criminal sanctions as a way to motivate people to change their behavior. In the 1980’s, mandatory minimums were used as a way to motivate people to stop using drugs: if you used, a judge imposed a long prison sentence. Today, criminal sanctions are used as a way to motivate people to enter treatment. That’s the idea behind drug courts (which Congress recently made $750 million available to expand): start treatment, consent to drug testing, and if you return to use, you go to jail.

But what if that assumption is wrong? What if the problem isn’t a lack of motivation for treatment but rather treatment access? Would that change how we police opioids? Chicago’s Narcotics Arrest Diversion Program, or NADP, offers us a chance to answer this question.

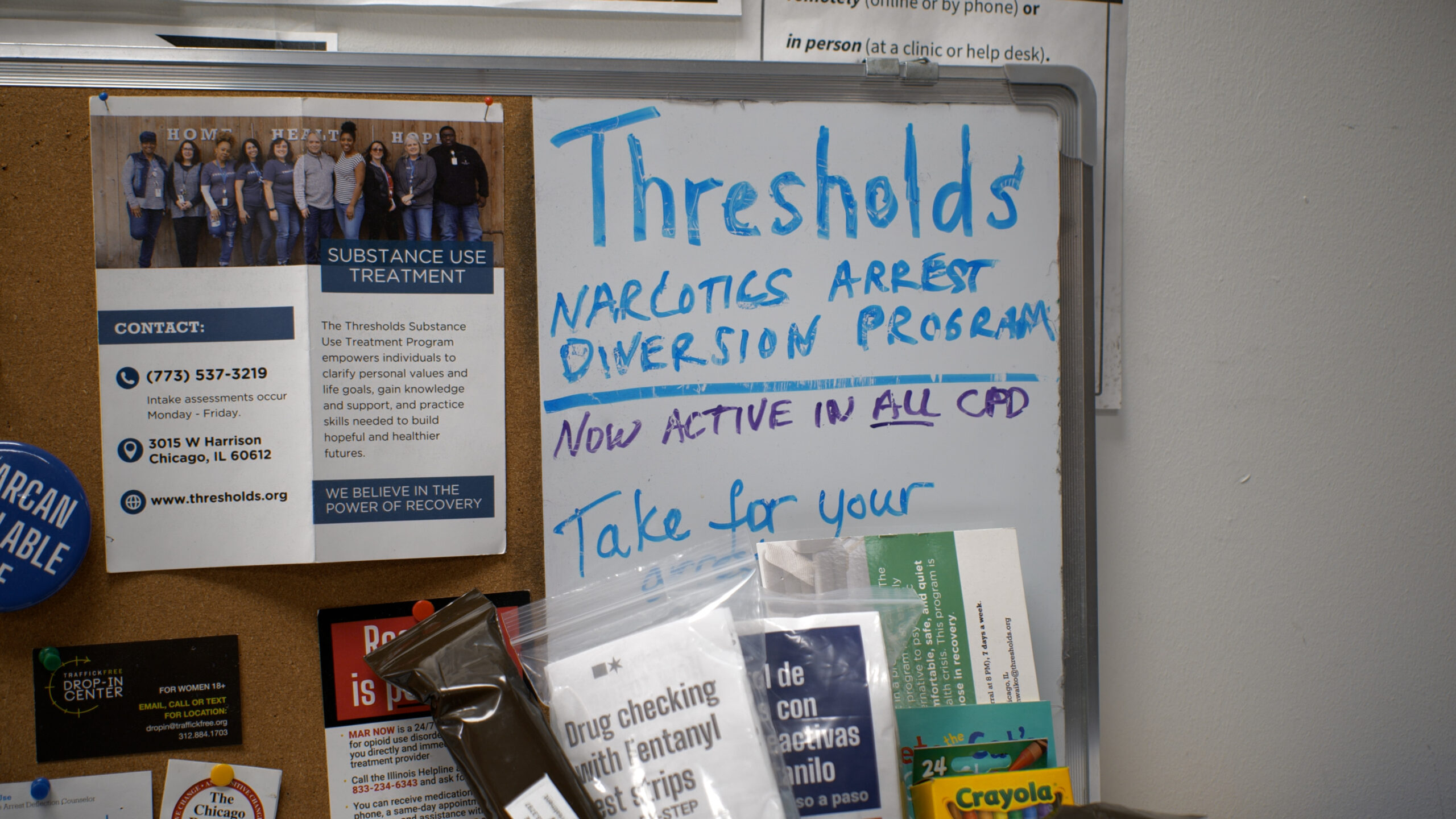

WHAT THE DATA SHOWS: NADP offers people arrested on non-violent, low-level drug offenses the opportunity to receive substance use treatment, including medication assisted treatment, instead of a criminal record or jail time. A partnership between Thresholds, the Chicago Department of Public Health, the Chicago Police Department, and Chicago-HIDTA, NADP is the nation’s largest sanction-free approach to policing drug use. The Crime Lab’s evaluation of NADP shows strong signs of success:

- High up-take: The program has connected over 1,200 people with treatment since its launch in 2018. 79% of people diverted began treatment, and participants were found to stick with the treatment over time.

- Reduced recidivism: Participants were 72% less likely to be re-arrested in the future, driven by a reduction in arrests for drug and violent offenses. These results demonstrate that enabling recovery instead of prioritizing punishment for drug use can simultaneously reduce the use of criminal justice system resources and increase public safety.

- Impact at scale: Participants are not formally charged with a crime and are not monitored for compliance with treatment, meaning NADP is cheaper and easier to scale than interventions like drug courts. In 2021, Chicago was able to roll out the program to every neighborhood in the city, and in 2022, the program’s eligibility criteria was expanded to nearly double the number of people who qualify.

WHAT WE’RE DOING: Our initial evaluation of NADP was just the start. We want to build on our learnings and inform the development of similar programs in jurisdictions across the country. For example, we now know participants are less likely to be re-arrested for drug use, but are they also less likely to overdose or to require emergency medical services for other drug-related incidents? The Crime Lab’s research team is currently seeking funding to answer these and other important questions to support data-driven policymaking in Chicago and beyond. We’re also working with the Mayor’s Office of Public Safety and project partners to develop a public dashboard that will provide real-time updates on how NADP is being implemented across Chicago.